In the final post in my “Ten Years a CCIE” series, I take a look at the age-old question: Is a CCIE really worth it? I conclude the series with some thoughts on the value of this journey.

I’ve written this series of posts in the hope that others considering the pursuit of a CCIE would have some idea of the process, the struggles, and the reward of passing this notorious exam. I would like to finish this series with a final article examining the age-old question: What is the value of a CCIE? In other words, was it worth it? All of the other articles in the series were written a couple of years ago, back when I worked for Juniper in IT, with only some slight revisions before publishing. However, this article is being written now (late 2016), in very different circumstances. I work at Cisco now, not Juniper. I work in the switching business unit, not in IT. I work in product management, and as a Principal Engineer have direct influence on the direction of our products. I specifically work on programmability, automation, and SDN solutions. As I write this, I see many potential CCIE candidates wondering if it is even worth pursuing a career in networking any more. After all, won’t SDN and automation just eliminate their jobs? Wouldn’t they be better off learning Python? Isn’t Cisco a company in its death throes, facing extinction at the hands of upstarts like Arista and Viptela?

Well, I can’t predict the future. But I can look at the issues from the perspective of someone who has been in the industry a long time now, and at least set your mind at ease. The short answer: it’s worth it. The longer answer requires us to examine the question from a few different angles.

Technical Knowledge

As I’ve pointed out in previous articles, during the CCIE preparation process, you will master a vast amount of material, if you approach the test honestly. But, as anyone in this industry knows, the second you pass, a timer starts counting down the value of the material you learned. On my R&S exam (2004), I studied DLSw+, ATM, ISDN, and Frame Relay. On my Security (2008) exam, I studied the VPN 3k concentrator, PIX, and NAC Framework. How much of that is valuable now?

True, I studied many things that are still in use today. OSPF, BGP, EIGRP, and ISIS were all heavily tested on the R&S exam even back in 2004. But how much of it do I remember? I certainly have a good knowledge of each of them, but even after taking the JNCIE-SP exam less than two years ago, I find my knowledge of the details of routing protocols fading away. If I were to take the JNCIE exam today, I would certainly fail.

Thus, some technologies I learned are obsolete, and some are not, but I have forgotten a lot. However, there are also technologies that I never learned. For example, ISE and Cisco TrustSec are huge topics that I am just starting to play with. Despite my newness to these technologies, I do have the same right to call myself a “Security CCIE” as a guy who passed it yesterday, and knows those subjects cold!

So, then, what about the value of the technical knowledge? Is it worth it?

First, it is because no matter what becomes obsolete, and no matter what you forget, the intensity of your study will guarantee you still have a core of knowledge that will be with you for a long time. Fortunately, despite the rapidity of change our industry is supposedly undergoing, networking is conservative by nature. The Internet is a large distributed system consisting of many systems running disparate operating systems and they have to work together. Just ask the guys pushing IPv6. The core of networking doesn’t change very much. You will also learn that even new technologies, like VXLAN, build on concepts you already know.

Second, even obsolete knowledge is valuable. Newer engineers often don’t realize how certain technologies developed, or why we do things the way that we do. They don’t know the things that have been tried and which failed in the past. Despite the premium our industry places on youth, old-timers do have important insight gleaned from playing with things like, say, DLSw+. It’s important for us not to simply wax nostalgic (as I am here) about the glorious days of IPX, but to explain to younger engineers how these dinosaurs actually worked, so that they can understand what decisions protocol designers made and why, and why some technologies fell into disuse or were replaced. And, millennials, it is your responsibility to sit up and listen, if not to seek out such information.

Technical “soft skills”

In addition to specific technical knowledge, CCIE preparation simply makes you better at configuring and troubleshooting in general. The hours of frustration in the lab and the broken configs that have you pulling your hair out ultimately help you to learn what makes a network break, and how to go about systematically debugging it. Certainly you can learn those skills elsewhere, but when you are faced with the challenge of building a lab in a short amount of time, you have to be able to think quickly on your feet. Even troubleshooting a live network outage doesn’t quite compare the intensity of the CCIE crucible, the eight hour slog during which one mistake can cost you months of studying. The exams where I took multiple attempts required me to seriously up my game between tries, and each time I’ve come out a stronger thinker.

Non-Technical Skills

Passing the CCIE exam honestly is a challenge, plain and simple. It requires discipline, persistence, extreme attention to detail, resourcefulness, ability to read documentation carefully, and time management skills. While you won’t pass the CCIE without having those skills to begin with, there is no question that the rigors of CCIE preparation will help to hone them. You will be a better person all around if you submit yourself to the discipline of passing the exam honestly.

It’s a bit like studying the martial arts. Most martial artists will tell you that, in addition to being able to deliver a mean axe kick to the head, they have achieved self-discipline and confidence from their practice of martial arts, and that they find these skills apply elsewhere in life. It’s true of any rigorous pursuit, really, and definitely true of the CCIE. Personally I have no doubt that the many hours of laborious study have made me a more detail-oriented and better engineer.

Employment value: Employee’s perspective

In my own case, my CCIE certification was directly responsible for my getting hired at Cisco TAC in 2005. It was absolutely essential for me to move to a VAR in 2007. Believe it or not, it was critical in my getting a job at Juniper in 2009, and having two CCIE’s and a JNCIE helped open the door to be re-hired at Cisco in 2015. Obviously, employers see value in it.

You still see CCIE certification listed as a requirement in many job descriptions. Without one you are cut out of those positions. Many employers see it as a key differentiator and qualification for a senior position in network engineering. VARs are still required to have a number of CCIEs on staff, so for some positions they will only talk to someone who has a CCIE.

Rarely is it the only qualification, however, and rarely is it enough, on its own, to get you hired. Shortly after I passed my second CCIE I got laid off from the VAR where I worked. I ended up interviewing at Nexus IS (now Dimension Data), another VAR, a couple months later. Having been out of work I was rusty, and the technical interviewer grilled me mercilessly. I’ve stated in the past that I don’t find this sort of thing productive, and I was uncomfortable, and didn’t have a great performance. Despite the fact that I had two CCIE’s, and despite the value of such credentials for a reseller, I got a call from HR in a few days telling me that they chose not to hire me. (These things often work out in the end; I am in a good place now, and I wouldn’t have made it here if I had stayed in the VAR world.) The entire experience reinforces a point I made in my Cheaters post: don’t think an ugly plaque and a number are a guarantee of employment.

That said, there is little doubt that a person with X skill-set and a CCIE is in a better place than a person with just X skill-set. As I said above, the certification simply opens doors. You cannot rely on it alone, but combined with good experience, the certification is invaluable. I would never have made it this far without one. Now it’s true that there are some very talented and knowledgeable engineers who don’t have, and in some cases disdain, the CCIE. Many of these folks do quite well and have successful careers. But again, add the famous number and you will always do better in the end.

Employment value: Employer’s perspective

Let’s turn it around now, and look at it from the perspective of a hiring manager. When I have the stack of resumes in front of me, how important is it for me to look for that famous CCIE number?

This is a much harder question to answer, and I’ve touched on some of the problems of the CCIE above. If you are looking at somebody who has a CCIE #1xxx, you know you are getting someone with age and experience. But if you’re looking for someone to do hands-on implementation work, will this be the right candidate? Maybe, of course, if Mr. #1xxx has been doing a lot of that lately. The point is, you can’t tell from the number alone.

Now let’s say you are looking at CCIE #50xxx. Does her CCIE number mean she will be the perfect fit for the hands-on job? Quite possibly, because she has a lot of recent hands-on experience. Will she be unqualified for the management role because she lacks the experience of CCIE #1xxx? Who knows?

The point is, from a hiring manager’s perspective, the CCIE is simply one piece of data in the overall picture of the candidate. It tells you something, something important, but it’s not nearly enough to be sure you are picking the right person. If you are hiring for a VAR and just need a number to get your Gold status, then the value of the CCIE jumps up a little higher. If you are just hiring a network engineer for IT, you need to take a host of other factors into account.

At the end of the day, I hope that people don’t make hiring decisions based on that one criterion. I had one job where we hired in a CCIE (against my advice) because the hiring manager believed anyone in possession of a CCIE number was a genius. (See “The CCIE Mystique”, here.) The guy was a disaster. Did he pass by cheating, or was he just good at taking tests? I don’t know. I’ve also known many, many extremely smart and talented network engineers who never got their CCIE, including several who just couldn’t pass it. Keep that in mind when you are getting overly impressed with the famous four letters.

SDN and the New World Order

I would like to conclude this post, and this series, with a few thoughts on the relevance of CCIE certification in the future. Various people in the industry, most of whom hold MBA’s in finance or marketing, tell us that CLI is dead and that the Ciscos and Junipers will be replaced by cheap, “white-label” hardware. Google and Facebook are managing thousands of network devices with a handful of staff, using scripting and automation. A CCIE certification is a waste of time, according to this thinking, because Cisco is spiraling down into oblivion. Soon, it will all be code. Learn Python instead.

I’d like to present my thoughts with a caveat. I’m not always a great technology prognosticator. When a friend showed me a web browser for the first time in 1994, I told him this Web thing would never take off. Oops. However, I have a lot of experience in the industry, and right now my focus at Cisco is programmability and automation. I think I have a right to an opinion here.

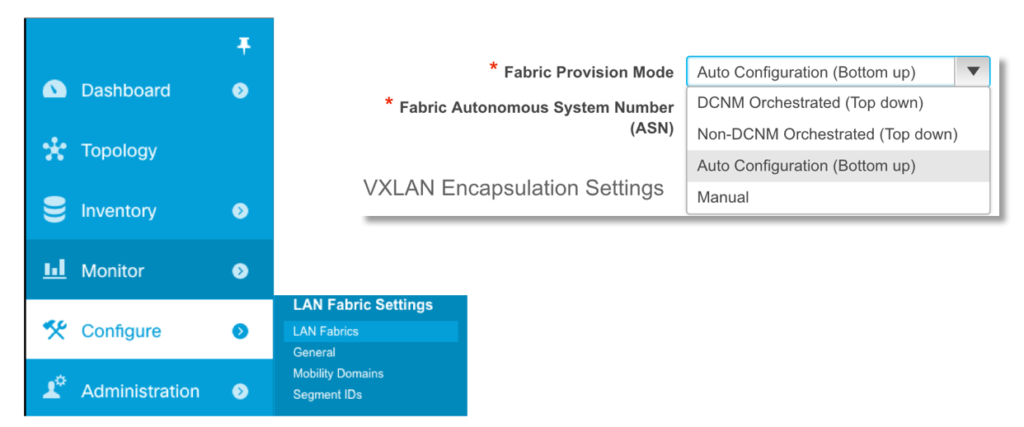

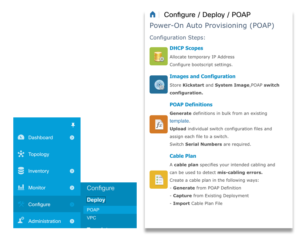

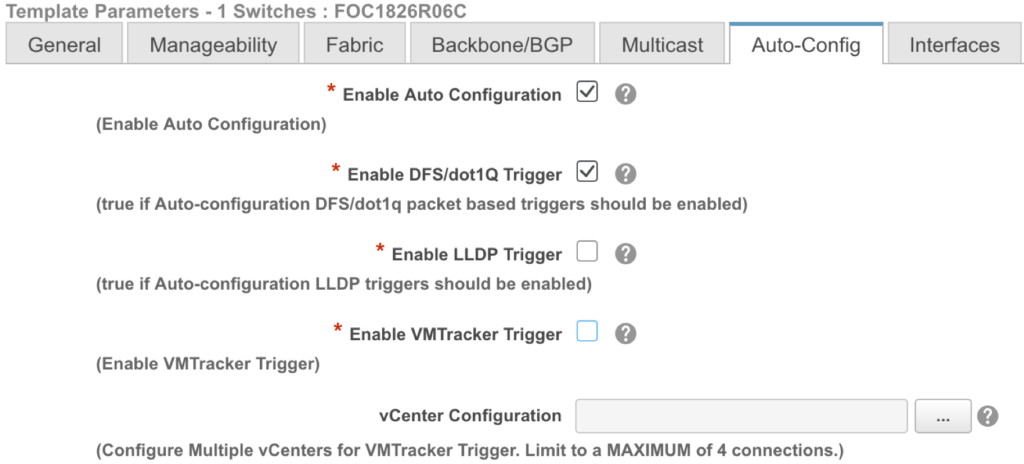

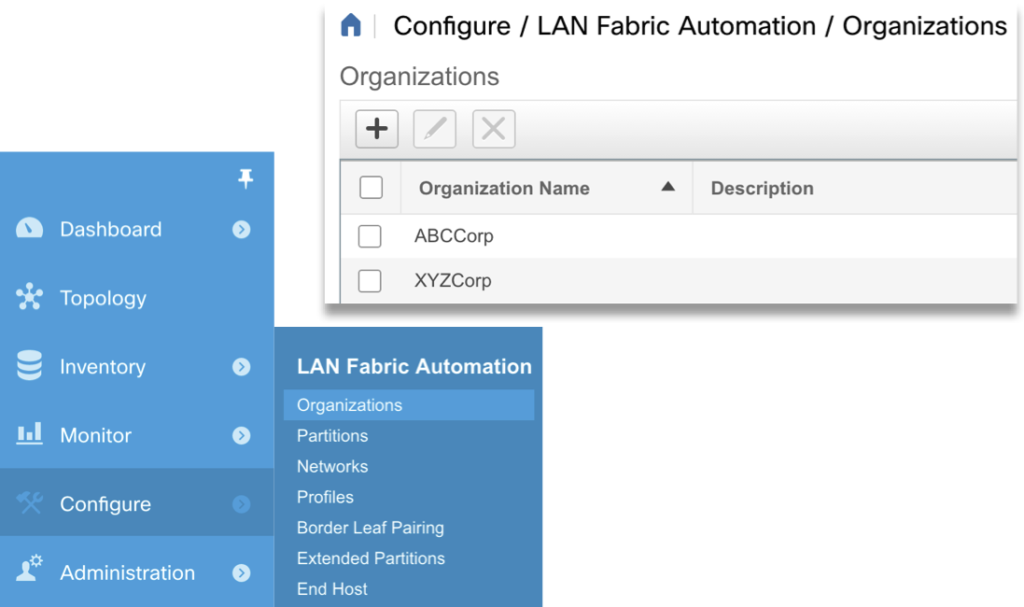

First of all, there is no question that interest in automation and programmability is increasing. All of the vendors, including my employer, are devoting a lot of resources towards developing and increasing their programmability and automation capabilities. I’ve spent my first year here at Cisco working on automating network devices with Puppet, Ansible, Python, and our own tools like DCNM. We’ve been working hard to build out YANG data models for our features. I barely touched Expect scripting before I came here! Customers are interested in managing their networks more efficiently, sadly, sometimes with fewer people.

Let me look at this from a wider perspective. As computing power increases, are humans redundant? For example, as a pilot I know that it’s entirely possible to replace human pilots with computers. Air Traffic Control could relay instructions digitally to the computers that now control most airplanes. With ILS and precision approaches, airplanes could land themselves at most airports. But would you get into an airplane that had no human pilots?

The problem is, even in the age of Watson, computers react predictably to predictable circumstances, but predictably badly to unpredictable circumstances. Many of the alleged errors that are introduced with CLI will still be introduced with NETCONF when the operator puts in the wrong data. Scripts and automation tools have to power to replicate errors across huge numbers of devices faster than CLI.

At the end of the day, you still need to know what it is that you’re automating. Networks cannot go away. If all the Cisco and Juniper boxes out there vanished suddenly, our digital world would come to a screeching halt. We still need people who understand what switches, routers, and firewalls do, regardless of whether they are managing them with CLI or Python. Look at the cockpit of a modern airplane. The old dial gauges have been replaced by flat-panel displays. Do you think pilots no longer need to study weather systems, aerodynamics, and engine operation? Of course they do! Just the same, we need network engineers, a lot of them, to make networks work correctly.

As to whether Cisco itself goes away, who knows? Obviously returning here, I have a great deal of faith in the company and its ability to execute. I think that a lot of the industry hype is just hype. Sure, some of the largest network operators will displace our hardware with Open Compute boxes. Sure, it will hurt us. But we are still in most networks and I don’t see that changing for a long time.

Closing thoughts, and a postscript

I began this series with an article on what I called, “The CCIE Mystique.” I don’t know if that quite exists the same way it did in 2001 when I started this journey, but I suspect it is still there a least a little bit. Those of us who have been through it have had the veil pulled back a bit, and we see it for what it is: a very hard, but ultimately very surmountable challenge. A test that measures some, but not even close to all of the skill required to be a network engineer. A ticket to a better career, but not a guarantee of one.

Being back at Cisco has been an amazing experience. This is the company that started my career, and that has built an entire industry. I’d be happy to finish things out here, but I have no idea in this age of mass layoffs whether that will be possible.

I had an interesting chat with the head of the CCIE route/switch lab curriculum not long ago. I must say, that for whatever complaints I have about the program, I was quite impressed with him and his awareness of where the program is strong and where it is lacking. I have no doubt that those guys work very hard on the CCIE program and it’s always easier to sit on the sidelines and complain. Ten years ago, when I started this journey, I wouldn’t have believed I would be at Cisco, helping to develop and market products, with a lab stocked full of gear, chatting with a CCIE proctor. Everyone’s path is different, and I certainly cannot promise my readers that investing in one certification will land them a pot of gold. There were a lot of other factors in my career trajectory. But at the end of a decade (actually 12 years as I write this), I can say that the time, money, and effort spent in pursuit of the elusive CCIE was well worth it.

As I close out this series I hope that my little autobiographical exclusion was not too self-indulgent. I hope that those of you who are new to the industry or studying for the exam got some insight from the articles. I hope that any other old CCIE’s who stopped by relived a few memories. Thanks for reading the series, and good luck on your studies!